Neglect brews Nota in coffee land: Araku emerges as highland for choosing ‘no candidate’ | India News

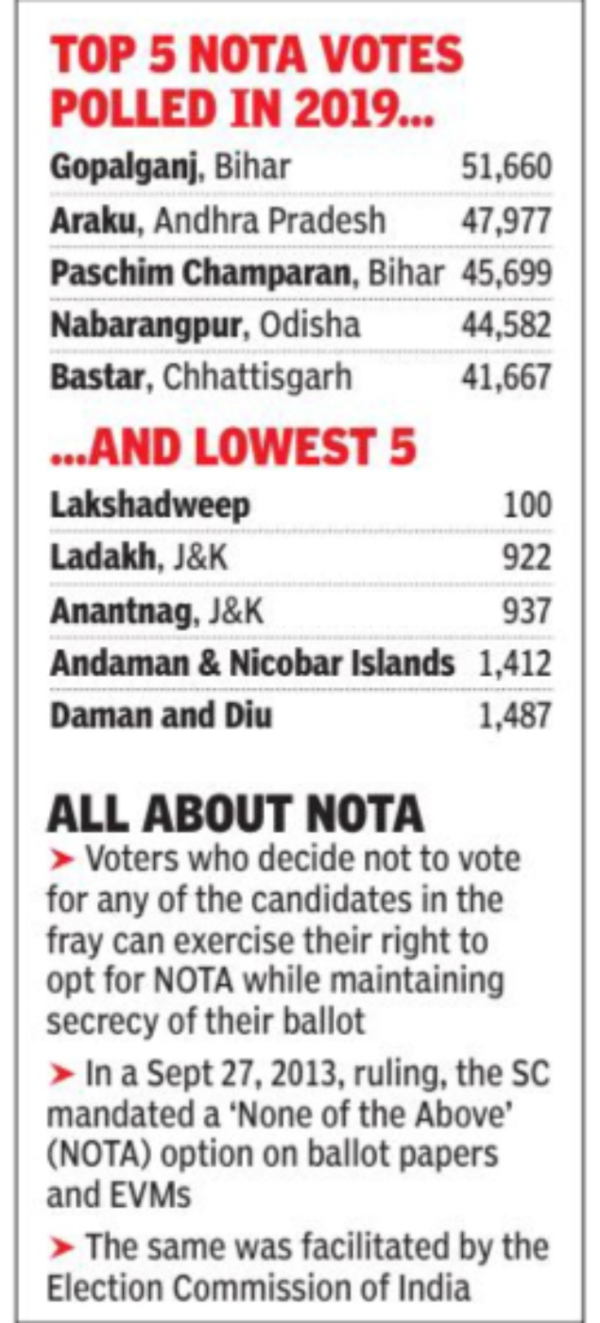

In the 2019 general elections, Araku Lok Sabha segment scored the second-highest Nota count in the country, with nearly 48,000 voters choosing that option on electronic voting machines (EVMs). Bihar’s Gopalganj topped the Nota count, with 51,660 votes.

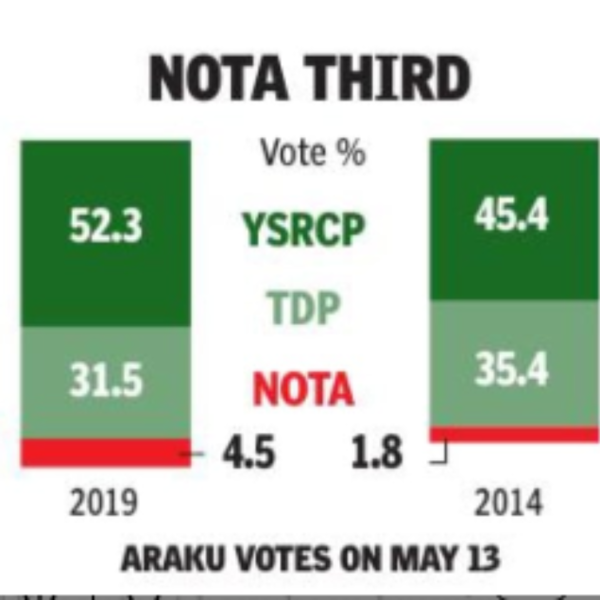

And though Nota votes could not sway the election outcome in Araku, as YSRCP’s Goddeti Madhavi won by a hefty margin of more than 2 lakh votes, they did manage to scoop up the second runners-up position in the constituency, indicating the significant presence and impact of voter dissatisfaction.

Image credit: A Sarath Kumar

In 2014 general elections too, Araku LS segment, which is spread across the tribal areas of East Godavari, Visakhapatnam, Vizianagaram and Srikakulam, notched up the highest Nota tally of 16,532 votes for any constituency in Andhra Pradesh.

So why is discontent boiling over in the land of India’s premium coffee? While Araku coffee has made it to cups of discerning coffee lovers world over, back home it has failed to lift the fortunes of tribal farmers. Also, locals say the daily struggle to navigate through the lack of basic necessities like roads, electricity, schools, safe drinking water, and medical facilities in several hamlets has found an outlet through Nota.

Last year, a pregnant K Roja died while being shifted to a hospital in a doli — a makeshift stretcher made of cloth tied to sticks—which is the only way villagers can rush patients to distant hospitals. Six years ago, a Rs 2-crore budget was allocated for a 7-km road connecting Ballagaruvu, Dayurthi, and Tunisibu villages. Construction remains unfinished. Similarly, a water project was sanctioned for Rachakilam village four years ago. A motor was installed but crucial pipelines were left incomplete.

The situation in Karriguda hamlet is even more absurd: a road exists but only on paper, forcing villagers to travel a backbreaking 15km to avail rations. Bonuru suffers a similar fate with an unfinished road. In Vankyapalem, children face the daily ordeal of an 8-km trek to school. Dozens of villages still lack electricity and plunge into darkness at sundown. This has forced many children to drop out from school and take up work alongside their parents.

CPM Andhra Pradesh state secretariat member Killo Surendra, who contested 2019 assembly polls from Araku, admits that long-standing neglect by successive governments has led to voter dissatisfaction and disillusion.

“Their struggle for education, health, roads, forest land rights, housing, electricity, and livelihood opportunities have compelled some to exercise their rights through Nota. Lack of awareness around EVM usage coupled with low literacy rates among tribals too could be a contributor,” he adds.

Going out to cast their votes too is a test of endurance. With no roads or a mode of transport, most villagers have to leave homes at dawn and walk for hours—at times 10-20km—through dense forests and rough terrain to reach the nearest polling centre.

To avoid this ordeal, many spend the night before the polls at relatives’ or friends’ places near polling booths. Some even sleep in the open, under trees, closer to polling stations. Despite these challenges, more than 74% of the electorate exercised their franchise in the 2019 general elections.

AP Adivasi Girijana Sangam honorary president K Govinda Rao says the stepmotherly treatment meted out to tribals has been reflecting in elections. “The increased share of Nota votes reflects the public mood,” he says.

Nyay Patra: Congress vows to scrap Agnipath scheme If voted to power

The usual election boycott call by Maoists is also a reason discouraging some, especially the elderly who cannot withstand the arduous trek and stay confined to their homes on polling days.

Doing their part, election officials have been setting up makeshift polling booths closer to villages to encourage turnout, but this has not stopped voters from pressing the Nota button.

Dr V Hari Babu, faculty member in Andhra University’s political science department, says though Nota cannot affect electoral outcomes, it often serves as a symbolic expression of voter protest and dissent. “The magnitude of Nota votes should be taken seriously as it may indicate several underlying factors such as hidden public dissatisfaction about their issues (not being addressed),” he points out.

The Araku assembly constituency, which falls under Araku LS segment, also emerged as a hotbed of democratic dissent in the 2019 assembly polls, becoming the only constituency to record over 10,000 Nota votes. Paderu, another tribal-dominated assembly constituency in the Araku LS segment, emerged runner-up with 7,808 Nota votes.

Among the top 10 assembly constituencies with highest Nota votes in Andhra Pradesh in 2019, nine were from Vizianagaram and Visakhapatnam districts, particularly the tribal pockets. While the 2014 elections saw 1.55 lakh Nota votes in Andhra, it surged threefold to 4.1 lakh in 2019.

Atul Tiwari is a seasoned journalist at Mumbai Times, specializing in city news, culture, and human-interest stories. With a knack for uncovering compelling narratives, Atul brings Mumbai’s vibrant spirit to life through his writing.