Louvre exhibition shows how Panchatantra went ‘viral’ | India News

Panchatantra’s cautionary tale of the dog with a bone – the one who mistakes his own image in the water for another dog with a better bone only to learn a hard lesson on how greed robs and corrupts – is etched in gold as part of a 14th century Iraqi manuscript currently on display at the Louvre Abu Dhabi (LAD).

Called ‘From Kalila wa Dimna to La Fontaine: Travelling through Fables’, the exhibition explores how Indian fables went ‘viral’ across the ancient world and were translated in many tongues to resonate through the ages.

The show hops from India’s very own animal tales compiled in the 3rd century to its Arabic descendant in Kalila wa Dimna, and all the way up to French fabulist Jean de La Fontaine’s ‘Selected Fables’ in the 17th century. Kalila wa Dimna was translated and compiled in the 8th century by one of the greats of Arabic prose, Ibn Al Muqaffa. His translation of the Panchatantra from Middle Persian later led to the Sanskrit text being rendered in Greek, Latin, Persian, Hebrew and Old Spanish among other languages.

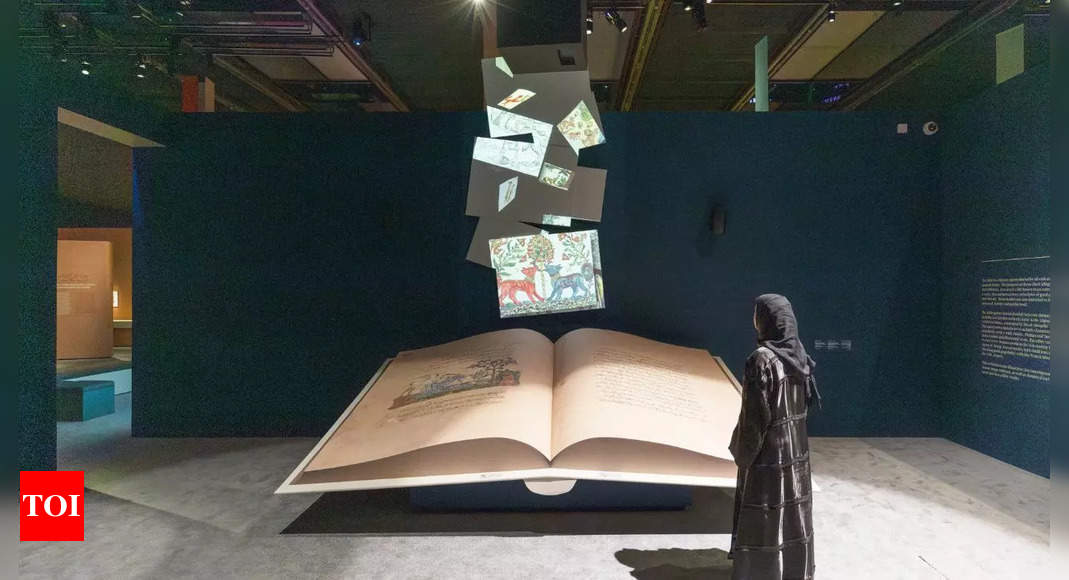

(Picture credit: : Ismail Noor/Seeing Things)

An 18th century manuscript of the Panchatantra is one of the exhibits.

LAD was born in 2017 after an agreement between the governments of Abu Dhabi and France, and envisioned as “the first universal museum of the Arab world”. “We are a storytelling museum; we speak the connected stories of our shared humanity. So, it makes a lot of sense for us to propose an exhibition dedicated to storytelling and fables. It’s a mirror of what we are,” says LAD director Manuel Rabaté.

Panchatantra champions principles of good governance, statecraft and lessons in power through anthropomorphic animal characters. So, the two jackals, Karataka and Damanaka – ministers to the lion king Pingalaka in Panchatantra – become Kalila and Dimna in Muqaffa’s Arabic translation. “I feel I have been living with the two jackals for a long time now,” laughs Annie Vernay Nouri, former chief curator at the oriental manuscripts department of Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF), which is one of the main collaborators of the exhibition. Nouri did years of research on Kalila wa Dimna and first thought of holding an exhibition on travelling tales almost ten years ago.

The exhibition features an 18th century palm-leaf manuscript of the Panchatantra and a 17th century Hitopadesha paper manuscript, both acquired from BnF. There is also a reproduction of an 8th century Indonesian sculpture depicting the Kacchapa-Jataka (The Talkative Turtle) which appeared in the original Panchatantra. The story of the talkative turtle and the two ducks appeared on Indian and Indonesian sculptures before the illustrated Arab manuscripts.

The exhibition also highlights how certain stories from Panchatantra were revised to align with prevailing notions of justice. For example, the Indian tale of the Lion and the Bull ends with the death of the bull. But in Kalila wa Dimna, Muqaffa adds a chapter where Dimna, who is responsible for the lion and bull’s fight, is judged and punished for his crime. Dimna’s trial is a perfect example of how anyone who acts badly will be severely punished. In Panchatantra, however, the law of the strongest prevails.

“Like Kalila wa Dimna, Panchatantra continues to be read and exists in several other forms – from cartoons to books, movies, theatre and even television shows. No original manuscript of Panchatantra survives but versions written and illustrated in the 17th and 18th century exist. I have seen the illustrated ones at Musée Guimet in their oriental collections department only recently,” says Nouri, saying it was a challenge sourcing the scattered remains of Panchatantra in existing manuscripts for the exhibition.

The LAD exhibition also features the Kalila wa Dimna manuscript in Arabic, the earliest known illustrated version produced around 1220 AD. There are over 130 other artworks on display — from rare manuscripts, paintings, to contemporary works, AI-driven-make-your-own-fable panels and more. They all depict narratives of friendship, loyalty, cunning and morality through the travails of envious cats, clever monkeys, devoted bears, quick-thinking rats and the like.

The cross-cultural spread of Kalila wa Dimna is often compared to that of the Bible. When it reached Fontaine – whose pithy tales continue to enrich French school curriculum – he acknowledged Panchatantra’s influence in his work filtered through Kalila wa Dimna. “The crusades had brought the European mind in contact with Indian works (Panchatantra and Hitopadesa) in their Arabic dress. Translations and imitations in the European tongues were speedily multiplied,” wrote La Fontaine’s translator.

BnF dates back to the 14th century. It was originally the library of the king of France but became a public library after the French Revolution. BnF hosts a huge collection of eastern manuscripts, from Arabic to Indian to those from the Far East, through a set of donations and acquisitions. “Fontaine, who was inspired by both eastern and western traditions of fables while writing his own, is as important a literary figure as French playwright Moliere. His fables, which schoolchildren learn by heart, promote basic morals and universal, secular values. Teachers ensure these values are well transmitted. Many artists, too, have been inspired by these fables,” says Emmanuel Coquery, director of Museum and Culture and BnF.

LAD also plans to have more exhibitions integrating India. “About 10-12% of our guests at LAD are Indians, as tourists and those living and working in the UAE. We have several Indian artworks in our permanent collection. On June 21, we have a big yoga practice under the dome of the museum. I am also pushing my team to launch a club dedicated entirely to the Indian friends of Louvre Abu Dhabi just like American Friends of the Louvre (AFL),” adds Rabaté.

‘From Kalila wa Dimna to La Fontaine: Travelling through Fables’ is on view at the Louvre Abu Dhabi till July 21.

Atul Tiwari is a seasoned journalist at Mumbai Times, specializing in city news, culture, and human-interest stories. With a knack for uncovering compelling narratives, Atul brings Mumbai’s vibrant spirit to life through his writing.